Just say the word. Baja.

Think of towering cordon cacti, grotesque elephant trees and winding boojum trees.

Baja. Imagine long-tailed man of war birds, sailing pelicans and plummeting brown footed boobies.

Baja. Dream about a remote wilderness peninsula 1280 kilometers long where the footprints of man are as scarce as rainfall.

Baja. The very name rings with adventure. And the name rang so loudly in my mind that I was compelled to experience it on my own.

PROLOGUE

Mexican Highway Number One chalked up another victim: a second class bus on an all-night journey from Ensenada to Santa Rosalia. The highway’s weapon was a well-placed pothole and its mission was to break bus axles. The mission was completed.

I sat on a guard rail and threw pebbles across the road to pass the time. Occasionally a car, jeep or truck would pass and I’d wave my thumb hoping to get a ride. No luck.

‘Stranded in the middle of the desert,’ I muttered to a Canadian traveller sitting next to me. ‘Now this is Baja.’ Travellers ten years ago would wait for days to be rescued. How long would I wait?

The sun had long since made its appearance. We had stopped suddenly at approximately five a.m. I figured it was now close to eleven a.m. Six hours had crept by.

‘I could enjoy being marooned along the coast or a village, but I sure don’t fancy being stranded in the middle of nowhere.’ Joe, the Canadian, threw a rock at a road sign. There was nothing but rocks and cacti surrounding us. Nothing to do but wait.

I was wondering why I or any other traveller or tourist would bother to come to Baja. The words of an early German missionary came to my mind. ‘Everything concerning (Baja) California is of such little importance that it is hardly worth the trouble to take a pen and write about it. Of poor shrubs, useless thorn bushes and bare rocks, of piles of sand without water or wood, of a handful of people who, besides their physical shape and ability to think, have nothing to distinguish them from animals.’

‘Look at them.’ I pointed to the Mexicans milling around the bus. ‘They’re so damn patient.’

It was nothing new to them. After living all their lives in the desert, they had evolved an extraordinary sense of patience. Everything they did was slow and easy.

Around the corner a dilapidated tow truck came bobbling toward us and turned around. A few minutes later, a bus followed. There were no cheers and few smiles. Everybody unloaded the crippled bus and piled into the replacement, and we were happily on our way down the highway.

Baja California is a 1280 kilometer finger-like Mexican state growing out of the state of California. It is a rugged peninsula landscaped with huge crags of mountains, barren deserts and lagoons surrounded by waving green palms.

In January of 1980, I came looking for adventure in Baja. I started the trip in Tijuana and travelled the entire length to Cabo San Lucas.

Day 1. 5 January 1980.

Tijuana. The gateway to Baja California. A circus with all the sins and ugliness of a border town. ‘And in this ring watch a drunk American get bounced out of a bar … and at center stage marvel at the incredible stupidity of a German tourist getting ripped off buying ‘authentic’ Mexican jewels. Buy this, buy that. Souvenirs here, curios there.’

Being only 27 kilometers south of San Diego, Tijuana is almost more American than Mexican. The Mexican government even found recently that US dollars were the common unit of exchange and not the Mexican pesos.

Tijuana is in a fearful race to modernity, with new boulevards and suburbs and a population explosion causing ever growing numbers of people to live in shanties and tin houses.

I sighed and oriented myself to the city and tried to get on a southbound bus as soon as possible.

Ah, but sweet, sweet bureaucracy has a way of delaying things. The rubber stamped crazed Mexican government feels that every tourist or traveller venturing beyond the border towns should have a worthless piece of paper they call a tourist permit. I didn’t have one, I didn’t know where to get one, and no one could understand my English or Spanish. I chose to walk back to the United States where I was understood.

I was eventually routed in the right direction and got the permit. The next step was to take the next bus out of Tijuana.

I put myself at the mercy of the Mexicans. I had no idea where to go to get the bus heading south. As a matter of fact, I didn’t know for sure if a bus to the south even existed. If not, I would cancel the trip down the peninsula and go somewhere else.

At the bus depot I learned that I could take a bus to Ensenada, 96 kilometers to the south. I had two hours to wait. I spent ten minutes walking the streets of the dusty, crowded city, then hid in the bus depot.

The highway to Ensenada was a fast and well-maintained toll-road. Was this going to be characteristic of all of Baja’s roads?

Ensenada. Another tourist town. Hopefully only a stopping point for a bus change. Once again I was confronted with travel decisions.

I had two choices. I could spend the night in Ensenada and take a bus to El Rosario, 150 kilometers south, the next day. Or I could take a ten p.m. bus to Santa Rosalia which would get me two-thirds of the way down the peninsula. As I studied the timetable and map, I was startled by a voice behind me.

‘Do you speak English?’

‘Yes, yes, I do. ‘ I turned and saw a young, bearded, blue-jeaned traveller. His name was Joe, he was from Manitoba, and he and his girlfriend Lisa were on their way to Guatemala.

They had missed their bus and were in a dilemma as to what to do. That made three of us.

After much debate, I decided to take the bus to Santa Rosalia. I knew the lack of time prohibited me from stopping at many of the towns, so I chose to concentrate on a few of the southern towns. Joe and Lisa joined me.

At ten p.m. we were on our way, sucked up in a stream of tourists dripping south from one of the most populous areas to one of the world’s most sparsely populated areas. Just like the thousands of others who annually visit the peninsula, I, too, became a prisoner in a moving, metallic, mechanized cage called a bus that entrapped me on a thread of asphalt.

I came to Baja for its natural attractions and to get a glimpse of the ‘beduino’ people living in the desert. I was thrilled about having the opportunity to travel in one of the last of North America’s vanishing and nearly forgotten wildernesses.

In Baja California and the Geography of Hope, Joseph Wood Krutch put me in the mood about what to expect. ‘Nature gave to Baja nearly all of the beauties possible in a dry, warm climate – towering mountains, flowery desert flats, blue water, bird-rich islands and scores of great curving beaches as fine as the best anywhere in the world. All of this has remained very nearly inviolate just because of what we call progress has never marred it. Baja has never needed protection because the land protected itself.’

That was written in 1967. What contributed to such splendor and resistance to progress? Inaccessibility.

But the Baja of 1980 is not the Baja of 1967. The difference?

La Carretera Transpeninsular Benito Juarez, also known as Mexican Highway Number One. An $80 million, 1620-kilometer lifeline completed in 1973. As I travelled this red carpet rolled out to lure tourists, I would discover how well the land could protect itself from ‘progress’.

Day 2. 6 January 1980.

Darkness hid the desert from my view, but when dawn arrived the aura of the desert came to life. Towering cardon cacti dwarfed the bus and me. Mountains oscillated like bouncing balls. And turkey vultures circled the barren desert patiently waiting for death.

But the life didn’t penetrate the glass and steel of the bus. It could have been a picture or a movie. I wasn’t experiencing the desert!

I was sitting in a synthetic cage sealed off from the real world. I couldn’t feel any sweat trickling down my back. I couldn’t rub my hands across the sharp spines of a cacti. And I couldn’t spit out the sand that would accumulate in my mouth. No, I was an incarcerated animal watching a passing parade.

You can’t experience, live and enjoy the desert in an air conditioned bus equipped with reclining seats and a piped in music. To know the desert you have to leave the cars and buses where they belong – on the highways and the parking lots – and discover the desert on foot.

With all the emphasis today on motor vehicles we seem to have forgotten our most reliable form of transportation – our legs. After all, has any place on earth proved inaccessible to the simple means of heart and legs?

We’ve become a society dependent on the automobile. Our second home is the family car. We sleep in it, watch movies in it, bank in it, eat in it, and make love in it. But one thing we can’t do is experience nature in it.

A full day slipped by, a full day of sitting in a stinking, crowded, confining bus. This was no way to travel. Baja California was sliding right by me and I couldn’t do a damn thing about it. I was a prisoner.

San Ignacio. We approached a quiet, little village flourishing with date palms. A romantic oasis contrasting with the dry, gray desert. A village that looked like it had ceded from modernization a hundred years ago. I felt like a lost desert miner seeing a mirage. This was what I came to Baja for.

But before I could get off the bus and breathe San Ignacio’s sweet, pure air, the bus departed.

The bus wound down precarious switchbacks and halted at Santa Rosalia, 22 hours after leaving Ensenada.

Santa Rosalia. Music, not radio music, but live music. Residents of the city crowded around the bus depot, the only place in town where anything was happening.

An Englishman, Kim, and an Australian, Gary, fellow survivors of the bus ride joined Joe, Lisa and me in a search for a place to sleep. After spending a night sleeping on the bus, we felt entitled to a good bed. We walked through the town and were surprised by the unusual clapboard houses with front porches. With the help of a Mexican, we found a cheap hotel for $2.50 a person.

Day 3. 7 January.

In the morning, I explored Santa Rosalia, a mining town whose golden days were well behind. Pyramids of tailings and rustling relics of locomotives are remnants of prosperous years in the 1800s when a French company exploited rich copper deposits. It offers no beaches and no luxury hotels, therefore it is unattractive to tourists and has been somewhat preserved.

I was keyed up to continue 48 kilometers to the south to the town of Mulegé. Guidebooks proclaimed it as a ‘small tropical town located near the beautiful Concepcion Bay and on a lazy jungle-like river. The town is small and dusty but it has palms, papayas and mango groves which add slightly to its charm.’

A perfect place to relax and absorb some of the Baja lifestyle.

We were told that a southbound bus would arrive at 1:00 P.M. We spent the morning exploring the harbor. Pelicans, gulls and other sea birds were in abundance as well as small crayfish-like crustaceans.

At the bus stop we lay on our packs as Joe played his guitar and sang a Neil Young tune. The Mexicans curiously listened. A first class bus arrived at 2:00, only an hour late, not bad.

Mulegé. At Mulegé we walked five abreast down a dusty cobblestone street. The town was geared for tourists. Modern ‘supermercados’ offered all the supplies tourists needed. At a market we bought bananas, dates, tortillas, cheese and meat. We felt it was only appropriate to also buy a bottle of Kahlúa, a Mexican liqueur made from coffee beans.

Earlier some travellers told us of a camping area out of town on the sea. We had no idea where the camping area was or how far it was. We just groped through the town and found a road leading along the river. A Mexican in a pickup truck offered us a ride along the potholed road to the coast.

I spotted the campground through an opening in the date palms. It was on the other side of the river! We weren’t about to walk the three kilometers back into town and we couldn’t cross the river. There was a dock at the end of the road so we sat there and yelled to some fishermen in boats asking for a ferry across the river. No luck.

I took off my shirt and soaked up some of the last rays of the sun. Gary suggested we open the bottle of Kahlúa and drink while we waited. No one protested.

Between rounds of Kahlúa, one of us might have waved or yelled at a fisherman. Actually none of us were too eager to leave. The sun was setting amongst the date palms and reflected its light off the lazy river. Sea birds frolicked in the last light while fishermen pulled in their nets. The moment was too great to worry about accommodations.

A Volkswagen pulled up and three Mexicans got out. Kim and I went to talk with them. None of them spoke English well, so I put my Spanish to the test. By speaking half Spanish and English and using gestures we got our points across and were immersed in laughter.

‘Cerveza?’ Roberto offered me a beer. After a couple of beers I noticed the sun had set, the temperature had dropped, and all the fishermen were gone. I guessed we were stuck there for the night.

I suggested our Mexican friends join us for some music and conversation. They happily accepted, but first, ‘más cerveza’ and they drove into Mulegé to buy more beer.

We gathered in a cove in the rocks to escape a cool breeze. Joe brought out his guitar and Lisa her harmonica. Our Mexican friends later returned with an overabundance of Tecate, a popular Mexican beer. For the remainder of the night, music and laughter echoed from the rocks. David, one of the Mexicans, played Mexican music on a cassette player and danced. Roberto built a fire of paper and palms.

It was an international gala. Among the eight of us were three Mexicans, two Canadians, one Englishman, one Australian and one American. Yet, despite all our differences we managed to fill the night with music and laughter.

Stars, undimmed by any manmade light, danced with us. The night was cold and I cuddled up to the fire. The third Mexican was an attractive señorita and I attempted to hold a conversation with her but only got a few smiles in return. But as she got up to leave the beer finally loosened my tongue and I suddenly became fluent in Spanish. ‘Un beso, por favor?’ I asked of her and got a sweet kiss which would linger on my lips till morning.

The night proved too long.

Our Mexican friends were driving to La Paz in the morning so I made arrangements for them to take Joe and Lisa.

After they left I took my sleeping bag and slogged along the beach and crashed under the twinkling desert stars.

Day 4. 8 January 1980.

At dawn, I woke up startled. Drums and bugles were playing reveille as if they were right on top of me. Yet I could see no one, except a fishing boat. I stuck my head out of my sleeping bag and could see that during the night I had thrown my sleeping bag on the beach right next to a military barracks. My bright blue sleeping bag contrasted strongly with the sand and was easily visible to anyone in the area but I just wasn’t ready to start the day so early. I stuck my head back in my sleeping bag and tried to snooze a bit longer.

Our Mexican friends didn’t show up, so we packed up and hiked toward Mulegé. After we were thoroughly exhausted, a jeep going our way stopped. I asked for a lift and all of us climbed aboard. Kim and Gary stood on the bumper and clung on.

The owner of the jeep, Javier, was a Mexican studying in San Diego. He was travelling all the way down the peninsula and agreed to take Gary, Kim and me to La Paz.

We found David in Mulegé and loaded the Volkswagen with five people and gear. Then we packed the jeep with four people and lashed the backpacks to the outside.

‘Now this is how to travel in Baja,’ I said to Gary as I crawled into the crowded jeep. A sticker on the dashboard read ‘Baja tested’.

I enjoyed the freedom of travelling in a private car and Javier was happy to stop for photographs.

The highway skirted Bahia Concepción, one of the most beautiful bays in the hemisphere. I had originally planned to get out and spend a few days there and enjoy some solitude. The seascape was stunning, but even more shocking was the abundance of caravans and motor homes that dotted the coast. Nearly every cove which had access to the highway hosted its congregation of campers. It became evident to me that Baja had lost its inaccessibility. I decided to continue on to La Paz with Javier.

‘Baja California is a wonderful example of what bad roads can do for a country,’ Joseph Wood Krutch wrote in 1967 about the inaccessibility of the peninsula.

In 1980, I witnessed what good roads can do for a country.

After millions of years of neglect, the paradise that once boasted of ancient solitudes and splendid seas, of tiny villages lost in time and of primal beauty is now fighting an onslaught of tourists, trailers and boomtowns.

The lure of the wilderness is drawing more visitors, some of them properly appreciative of a unique desert peninsula, but too many thoughtless and destructive. The caravans crowd the highway, gobble up huge amounts of gasoline and create unsightly piles of litter along both sides of the narrow highway.

Discouraging evidence of man’s intrusion is manifested in places which until recently were inaccessible. Rocks are daubed with graffiti or with paint to mark the route for off road car races. And discarded clothing, blown tires and broken fan belts find a home amongst the cacti.

When Krutch travelled in Baja, the roads acted as a filter. Only those travellers truly appreciative of wild places, solitude and silence ventured off the blacktop.

Now anybody with the time and money can drive the entire length of the peninsula. Or if they don’t drive, they can fly into a number of international airports or smaller airports and strips all up and down the peninsula.

Or they can take a ferry complete with a discotheque to three of the coastal cities. The peninsula has been opened up to people who seek from wild areas only fishing and sun tanning.

I wondered how many people parked along the beach ventured any distance from the coast.

I wondered if any of them knew of the endemic flora that grew in their backyard. And I wondered if any of them cared that Baja California was suffering from a formidable force named Industrial Tourism.

We drove past Bahia Concepción without swimming in its turquoise water or walking along its pristine beaches. We just drove and drove and drove and watched Baja from the inside of a jeep.

After travelling 500 kilometers south of Mulegé we arrived in La Paz. I had travelled nearly the entire peninsula in three days. A frightening sense of always travelling yet never reaching overcame me. When was I going to arrive in Baja? Where was Baja?

Dammit. Baja California was to the north. I missed it. I got sucked up in a flowing stream of humanity and drowned. I was just another tourist here for the sights. I was every bit as much an intruder as the business executive who flies in and travels nowhere except between his hotel and the beach.

Hell, I wasn’t experiencing Baja. I came to find the natural but instead I was finding something much more artificial. Where was Baja? Where did it go?

In La Paz we rendezvoused with Joe and Lisa. Baja dust coated our clothes and backpacks. We seemed out of place in this busy center of resort activity. Gorgeous Mexican women walked by dressed in long flowing dresses. Their sweet perfume overpowered the stench emitted by our bodies. We walked the streets of the enchanting old city awed by its inconsistency with the rest of the peninsula. With its tree-shaded lanes and Victorian style public building, La Paz retained some of its colonial heritage. Stores boasted of bargain prices for silks, perfumes and unique imports from many other countries.

We wandered the streets until we found a hostel with fair prices.

Kim, Gary and I ate our supper at a small café. There was no menu so Gary asked, ‘Que tienes?’ What do you have? When the woman said something that sounded unfamiliar, I ordered it. I was given a quesadilla, a grilled cheese tortilla.

The Mexicans were receptive to our attempts of Spanish and enjoyed it as much as we did. A man bursting out of a dirty t-shirt teased us. Laughter filled the cafe. The man gave Gary a cigar as a gift. I imagined that few foreigners frequented his cafe. There was an elegant restaurant next door.

After supper, Kim and I took a pleasant stroll along the seaside. We stopped at a small café for a soda. No one was in the café except the owner, his wife and his son and daughter. We had a long chat with them and used the children as interpreters.

Day 5. 9 January 1980.

Despite its splendor and comforts, La Paz wasn’t the city for me. My companions of the past several days – Joe, Lisa, Kim and Gary – decided to stay in La Paz. But I was still determined to find the real Baja that Krutch wrote about so I set off on my own. Once again I was drawn south, below the Tropic of Cancer, to land’s end at Cabo San Lucas.

It was a long four-hour bus ride to the Cape even though it was only 230 kilometers. I was on the postal bus and we stopped in every village along the way. I met two young travellers from Vancouver, Jean and Mariann, who made the trip less painful.

One of the villages we stopped at was San José del Cabo where the Mexican government is spending $50 million on a resort project that should supply 3,000 first class hotel rooms and 300 villas. It’s a village whose population will rise from 10,000 to 30,000 in the next four years.

At Cabo San Lucas, Jean, Mariann and I found a campground which catered mainly to motorhomes. I would have preferred to camp on the beach, but in a campground I felt more secure leaving my tent unattended while I explored. We found a grassy area and another vagabond, Daniel, who was also from Vancouver and had been camping at Cabo for several days.

I set up my tent then walked into town. I browsed in a modern supermarket frequented only by tourists. The cash register rang up more and more money. Tourists’ money.

Without a doubt, Baja’s Red Carpet has lead to a rapid change in the local economy. The highway was built for economic reasons.

Environmentalists and preservationists questioned the highway. But the Mexican government went ahead with the construction. Baja California Governor Milton Castellanos said in 1975 ‘we cannot accept the concept that, in order to protect the environment, the highway should not have been constructed. Such a sacrifice to progress is not possible.’

But what is progress? Is progress the electricity, telephones, television, fresh food, health services and jobs the road has brought? Are these things really improving the quality of 1ife?

Or is preservation progress? A dictionary definition of progress is the ‘advancement toward a more desirable goal’. Is it more desirable to have a threatened environment that may take hundreds of years to heal and to have half-witted tourists milling about your village looking for the nearest gasoline station? Is this progress worth the luxury of modern day societies or are the people of Baja California better off the way they lived twenty years ago.

Tremendous changes have occurred in Baja over the past several years. ‘We’ve gone overnight from the donkey age to the jet age,’ said Juan Manuel Mancera, the Tourism Ministry’s delegate in Cabo San Lucas. ‘It takes time to adjust, but we won’t be given that time. Things are moving too fast.’

I left the store and walked down to the beach. The setting sun created a pink tinge on the water. Scores of sailing boats lay anchored off the coast and hordes of noisy, littering people living in campers were on the shore cooking their supper. It was a depressing scene.

In my own selfish point of view, I would rather have not seen the highway built. I would rather see Baja from the, back of a burro or on my feet than from the reclining seat of a bus. But I am part of a minority. All those ‘wheel chair explorers’ devouring their supper are the majority and are dependent on the highway.

We have a dilemma in our hands. We can offer maximum accessibility for those with motor homes fully equipped with toilets and television. Or we can offer minimal accessibility and cater to those who seek solitude and unspoiled nature.

It is difficult to satisfy the needs of both at the same time. The developers –the majority – emphasize ‘providing for the enjoyment’. The preservationists – the minority – stress ‘leaving it unimpaired’. Both are in the name of recreation.

Aldo Leopold, a noted conservationist and author of the ‘Sand County Almanac’ wrote, ‘recreational development is not a job of building roads into lovely country, but of building receptivity into the still unlovely human mind.’

Would those people on the beach and the people hiding in their hotels be receptive to a roadless Baja?

A solitary road through a desert peninsula may, not appear to be too devastating, but one road brings more roads and more development. Leopold foresaw the problems involved in constructing highways. ‘Bureaus build roads in new hinterlands to absorb the exodus accelerated by the road … To him who seeks in the woods and mountains only those things obtainable from golf or travel, the present situation is tolerable. But to him who seeks something more, recreation has become a self-destructive process of seeking but never quite finding, a major frustration of mechanized society.’

I ate dinner at a cheap restaurant, then crawled into my tent early. Noisy cars and talkative humans prevented me from falling asleep and getting any desert solitaire.

Day 6. 10 January 1980.

A rooster woke me up before dawn. Daniel directed me to a bakery where I bought some bread fresh out of the oven.

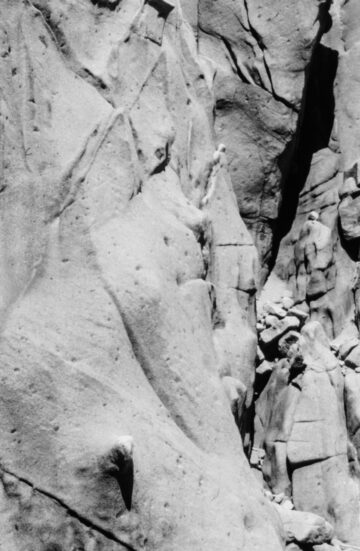

I wanted to escape for the day so I hiked up the coastline far away from the hustle and bustle of Cabo. I found an isolated spot on the rocks and wrote notes and postcards, played harmonica, sang songs, took photographs and listened to and watched the ocean. The power of the ocean as it struck the rocks below me was at times frightening. Behind me the wind had carved faces in the rock that gave me a sense of being watched.

Except for a few passing boats, I came in contact with no one. I almost felt I was in a wilderness.

The value of wilderness is sometimes underestimated. Just like many other things we take wilderness for granted – until we have none left.

Imagine a world with no wild places. Where would you go to escape the artificial jungle and the tense lifestyle of the city? Where would you go to seek the origins of man? Where would you go to witness the unduplicated majesty of a soaring bald eagle if none existed? Where would you go to preserve your sanity?

Without wild places, writer Edward Abbey believes, all men would turn to lives of crime, drugs and psychoanyalsis.

A ‘small dark cloud’ named Progress is enveloping wild areas, including Baja California. Some say it will improve the quality of life; others such as Aldo Leopold disagree. ‘Now we face the question whether a still higher “standard of living” is worth its cost in things wild and free. For us the minority, the opportunity to see geese is more important than television and the chance to find a pasque-flower is a right as inalienable as free speech.’

The sun was beginning to set; a welcome relief to my sunburnt body. I had patiently waited for the sunset in order to photograph it. Finally the sun was at the right angle and I lined up my shot.

DAMN. My camera malfunctioned due to saltwater. After I realized my camera was beyond immediate repair I saw no reason to remain and left without watching the climax of the sunset.

It occurred to me that I had been seeing Baja, and the rest of the world where I had travelled, through the lens of a camera. When I looked at an object I thought only of lighting, depth of field, shadows, composition and exposure.

I was burdened by a mechanical device that shut off my senses. I was victim of the tyranny of film. I didn’t appreciate anything unless it was photogenic.

But now, I felt a heightening of my senses. I would bury the camera in my pack and open my eyes to Baja. With a camera I too often photographed and forgot. Now I was going to take a long look at everything and place an image of it on the emulsion of my memory.

Day 7. 11 January 1980.

In the afternoon, Daniel, Jean, Mariann and I went to the beach for a swim. We walked away from the tourists and were rather stunned by the sight of a Mexican fisherman filleting five large sharks and eight to ten small sharks. He told us he caught them close to shore. We looked out at the sea and decided it was too cold to swim.

I would begin my long trip home on the next day so I spent the afternoon in camp and hand washed my clothes so I’d look presentable while hitchhiking. I had the Baja Blues and was feeling depressed and didn’t feel like doing anything so I just sat around camp and watched my clothes dry under the desert sun.

Day 8. 12 January 1980.

The time had come for me to make a U-turn and begin the long and difficult 5,000 kilometer trip home. But I was eager to leave Baja. I was dissatisfied with my travels and Baja. The trip just hadn’t gone as I had naively planned it.

I boarded a bus in Cabo heading for La Paz and sat next to an American couple … the first Americans I had met on the trip. Dan and Susy were from Colorado but quite coincidentally Dan’s brother was living near my tiny hometown of Amery, Wisconsin. Dan and Susy were the only Americans I travelled with but that didn’t mean there were no Americans in Baja.

The Baja I had seen appeared more American that Mexican. By declaring it a duty-free zone, the Mexican government has encouraged the entry of American goods. And by creating a new trust mechanism, it has enabled foreigners, mostly Americans to circumvent a constitutional provision limiting ownership of coastal lands to Mexican cities.

Now Americans can come to the southern tip of Baja and never be far away from home.

Food is flown in from California, fellow guests are invariably Americans and Spanish is rarely heard outside the kitchens of the hotels.

I failed to find the real Baja. I lacked an essential prerequisite: time. I spent only eight days – a finite amount of time. To travel in Baja requires an unlimited amount of time. Time to wander off the highway; time to wait patiently for late buses; and time to sit, relax and contemplate.

Eight days in Baja gave me only a superficial look. I consider it only a teaser; a background of the peninsula to prepare myself for an expanded expedition later.

I was hoping to catch a ferry from La Paz to cross the Gulf of California and arrive at Topolobampo on the mainland. From there I wanted to go inland and ride the famed Copper Canyon train in the Sierra Madre Occidental.

In La Paz I bought bananas, oranges, figs and guavas for my voyage across the Gulf of California. I searched for a way to get out to Pichilinque, the port eight kilometers away where the ferry landed.

Getting from A to B in Baja simply wasn’t easy and nothing worked out as planned or anticipated. I had been told in Cabo that the ferry to Topo would leave at 5 PM that afternoon. Upon arriving in La Paz I learned that the ferry left at 8 but not today, tomorrow. ‘En la mañana?’ I asked. ‘Si, si’, the man replied. Next I learned that there was no bus going to the ferry port that afternoon. I decided to hitchhike to the port and crash there for the night so I would be sure to be there for the morning ferry.

After a ten-minute wait, I was offered a ride by a Mexican family taking a friend to the ferry port. José told me the ferry would leave the next day at 8:00 PM, not in the morning as I understood. ‘Mañana’ is Spanish for both ‘tomorrow’ and ‘morning’ so I got it all wrong with 8 in the morning. He was taking a 5:00 PM ferry to Mazatlán which was considerably south of Topolobampo.

I didn’t feel like spending over 24 hours at the port till 8 PM the next night and I didn’t want to turn back to La Paz so I said ‘what the hell’ and joined José on a voyage to Mazatlán.

José led me through the ordeal of buying a ticket, boarding the ferry and finding my seat. I bought the salon class ticket, the cheapest, for a mere $5.00. The voyage would take 16 hours. The ferry was equipped with a café, nightclub and discotheque.

The 800 ferry passengers were Mexicans tourists except for three European vagabonds and me. José gave me a grand tour of the ferry. We sat down on a bench on the deck next to a person who was sleeping under a blanket. When I sat down, the blanket came off and revealed a gorgeous Mexican woman. She started talking to José and I could hear her asking my name. I smiled at her and instantly had no regrets about missing out on my Copper Canyon trip as I would end up spending the next few days frolicking with her on the beaches of Mazatlán.

At that moment, however, my thoughts were not on what lay ahead, but what lay behind. José and I walked up to the deck and watched the Baja peninsula slip away. I wondered if I would ever return and if I did what changes would occur. Baja California is a paradise in peril. It has lost its charm; the highway has destroyed its magic.

But is it a paradise lost?

Will Baja California become another Hawaii, Bali or Fiji?

It doesn’t have to. With a bit of foresight, the Mexican government can place restrictions on incoming traffic and development. More land can be set aside as wilderness areas and national parks. More education of tourists and hosts can occur. But most importantly the Mexicans must ponder the question of what is progress and what determines the quality of life.

The Baja that Krutch wrote about is still there. Some parts are still as they were when the first Spanish explorers arrived. Isolated fragments of wilderness can still be found, but you have to wander far off the highway. But you’d better hurry. At the present rate of development, there’s no guarantee how long it will be before Industrial Tourism conquers Baja.

There could be hope. Krutch writes, ‘All the other and varied attempts to “develop” the area have ended in dismal failure, for the land itself has always returned to its own wild self.’

Mr. Krutch, from my own selfish point of view, I hope you’re right.