While a grad student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I took a course on tropical agriculture and studied under the great Amazonia scholar Dr William Deneven. I was mesmerised by his tales of the Amazon. And so was my classmate, Oliver Coomes, who decided to write his PhD dissertation on the riverine peasants – the ribereños – of a tributary of the Peruvian Amazon known as the Rio Tahuayo. When class wrapped up for the summer Oliver got ready to leave for a year of research in the Amazon. I told him I’d come and visit him. ‘Sure,’ Oliver said. But no doubt he thought ‘fat chance’, I’d never make it.

A couple of months later I was in the Amazon port city of Iquitos and was knocking on his door. Oliver and his wife, Carmen, were in Iquitos to re-supply and were about to head back upstream to the Rio Tahuayo and said I was welcome to come along.

I had a few days while the Coomes got ready and so I explored Iquitos. I checked out the floating markets and strolled through the busy and chaotic streets of the port town. The city was no longer the vibrant place it was in the early 1900s when it thrived from the wealth of the rubber boom. There were signs of past splendour in the city but largely it was a fairly sleepy town in 1989.

One day I was walking through a neighbourhood of ramshackle shacks – what the Brazilians would call a favela. I saw a group of people gathering around and looking at something. I squeezed my way into the crowd and saw the object of their attention. There was a man lying on a narrow dirt path … dead. I asked the man standing next to me ‘Qué pasó?’ but don’t remember his response. The dead man might have drunk himself to death or was stabbed to death or had a heart attack. I don’t remember. But I remember clearly what I was thinking. I was clutching my camera and just wondering ‘Should I take a photo?’. I was a budding photojournalist and thought it would make a great shot of life in the wild and lawless port town of Iquitos. But for some reason I didn’t. I just didn’t feel it was the right thing to do. I paid the dead man my respects and continued my exploration of the barrio. I never became a photojournalist and often wonder if it was at that moment I realised I didn’t have what it takes.

Oliver and Carmen loaded up provisions in the Delphin – a small boat which would take us upstream to the villages on the Rio Tahuayo. Oliver enlisted a local named Antonio who served as our boatman, cook, fisherman and cultural broker. We putt putted up the river and I sat and absorbed myself in life on the Amazon. Boats of every size and shape and degree of ‘flotability’ passed us … all leisurely cruising along at Amazonia pace, nice and easy.

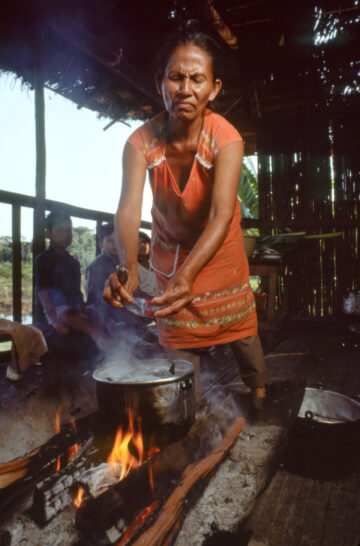

We arrived at a village on the blackwater tributary, the Rio Tahauyo, and were welcomed as guests at the hut of a family. We were famished but never went hungry as there was always some piranha in a pot on the wood stove.

All of that piranha was playing tricks with my stomach and I had loose bowels. There was a bit of a village latrine – a couple of boards placed over a ravine. Perfect for squatting and an adequate drop to ensure fresh air at the dropoff zone. The ravine was open and the village pigs were at the bottom eagerly awaiting a feed. I squatted and looked between the board and much to my horror a pig lined himself in the direct line of descent and was looking up at me awaiting breakfast. I tried to shoo him but my bowels were rumbling and I couldn’t delay. Bombs away. And then SPLAT. Got him right between the eyes. The poor pig didn’t have a chance. The next day I thought I’d give the village latrine a miss and headed out to the woods to do my business. I made myself comfortable and once again to my horror the pig found me. The same one! And how did I know? Because he still had my gringo s**t right between his eyes.

We spent a few days in the village and joined the locals in their work and Oliver collected data for his research. We watched our host work on his dugout canoe, watched other clears the rain forest for planting and joined a ‘minga’. A minga is a communal work party where the villagers joined forces to plant a recently slashed and burned area with maize. After spending exhausting days out in the fields, we’d come back to the hut and slept soundly in hammocks.

I enjoyed staying in that village on the blackwater tributary. Life was slow and simple; just my pace. I felt comfortable with the villagers who found it amusing that I would always want to point a camera in their face. But it wasn’t an easy life for the villagers. They worked hard at subsistence agriculture sprinkled with a bit of market-oriented agriculture to provide some cash for those things that nature couldn’t provide. I felt for privileged that I had an opportunity to have a glimpse into their lives.

Oliver decided to take a break from his research and we travelled further upriver to the Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve. The Pacaya-Samiria is the second largest reserve in the Amazon and at the time was very rarely visited and had virtually no infrastructure. It occupies 1.5% of Peru and protects a ridiculously rich pool of biodiversity including more than 500 species of birds and 100 of mammals (including the pink dolphin). Like all protected areas in developing countries it was struggling to protect its biological riches due to pressures from all aspects of ‘development’.

Two years after I visited, the reserve made news as Texan oil companies were offering the Peruvian government big money to give them drilling rights in the reserve. I believe the Peruvian government saw the long-term gains in the preservation of wildlands and did not sell out for the short-term economic gains. I’m not sure what pressures the reserve is under now but eco-tourism has arrived and now a travel lodge brings in tourists. With a biodiversity as rich as the Pacaya-Samiria has surely eco-tourism would generate more long-term wealth for the Peruvians than some drilling rights.

We sat in our little boat for hours as we ventured deeper and deeper into the reserve and soon I was getting delirious from the endless walls of green lining the river and the constant shrill and screams of insects, birds and frogs. As we rounded another bend in the river that solid green wall was broken by a flock of great egrets. I had to pinch myself to make sure I wasn’t dreaming about being in the inner depths of Amazonia and that I wasn’t watching a National Geographic rerun.

At dusk we arrived at the post of the lonely park guards who were very keen to have some visitors. In the tropics you are constantly hot and sticky but I didn’t go for my evening bath in the river. While we were on the Rio Tahuayo I’d bathe in the river and the piranhas would nibble harmlessly on my toes. But here in the Pacaya-Samiria the piranhas just seemed bigger and hungrier and the truth is I was simply afraid to plunge into those black Amazonian waters not knowing what lurked beneath.

Instead of the piranhas eating me, the park guards fished a few out and we ate them for dinner. The fish wasn’t enough to satisfy the hunger of the park guards and they went out at night to dig up eggs of nesting river turtles. That seemed a bit hypocritical to me for park guards to do that but it was typical of guards in developing countries where they are so poorly equipped and provisioned that they have to scrounge for food.

Eventually, we returned to Iquitos and I was extremely gracious to Oliver and Carmen for letting me see a part of the Amazon which few would ever get the chance to do. Oliver finished his year in the Amazon and finished his dissertation. He is now a professor of geography at Canada’s prestigious McGill University. I continued south to the old Inca capital of Cusco, then Machu Picchu and Bolivia’s Lake Titicaca. All magical names which once rang out in our living room on Sunday evenings while watching National Geographic.

Back to 2016, and I’m thinking of the Amazon and thinking of its importance in maintaining the delicate balance of carbon in our atmosphere … and then thinking that an environmentalist’s worst nightmare was just elected as President of the United States who is threatening to reverse the hard work of 190 countries to ratify COP21 … and thinking that a climate change denier could soon become the head of the US Environmental Protection Agency and threaten environmental catastrophe on the entire planet … and thinking of the wonderful legacy that President Barack Obama will leave in his fight on environmental issues … and SNAP … get back to 1989, Mike, think of that majestic, slow river, the laid back ribereños, that pig with my s**t on his forehead, the graceful great egrets, nice thoughts, calm, soothing thoughts…escape…escape…