Day 1 – 28 March 1981

Lagos de Montebello to Huistan on the Rio Delores

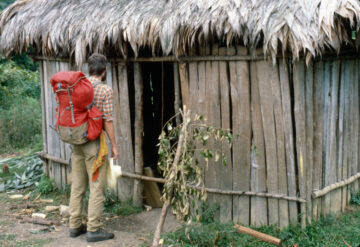

They were the best tortilla I had ever eaten. Made of freshly ground corn, they were thick, yet not tough and still warm. I folded one and used it as a spoon to scoop up the scrambled eggs served in a bowl of hot water with onions and tomatoes. An Indian man and his son silently sat on a stool, shelling beans, and watched my companion, Hans, and me clumsily try to use the tortillas as spoons. He no doubt wondered why two gringos would be passing through his remote jungle village in southern Mexico. His young wife, wearing the traditional clothes of her tribe, her glossy braided black hair running down the length of her back, peeked at us through the gaps in the hut. Did the foreigners approve of the food she prepared, she wondered?

We did and paid her generously.

After supper, Hans and I walked down the wide, grassy streets of Huistan in the last light of the day toward our camp on the Rio Delores. Indians bathing in a creek stopped lathering, watched us and returned our greeting. We then all turned to watch a flock of white egrets sail through the dusky haze. The setting sun seemed to trigger a wave of silence through the valley. I lay on the bank of the Rio Delores. The song of the river began to drown in a crescendo of insect and frog voices. Jupiter and Saturn, closely aligned, appeared in the sky. Could this tranquil jungle be the same jungle that was so hostile earlier in the day?

Hans joined me on the river bank and lay back and enjoyed the quiescence. ‘The new highway will pass 200 metres downstream,’ he said. I nodded and understood. Change was on its way to the Selva Lacandona.

In their mad race to modernity and prosperity, Mexico was building highways to develop remote areas. But here in Mexico’s southernmost state of Chiapas, I was one step ahead of the highway crews … but barely.

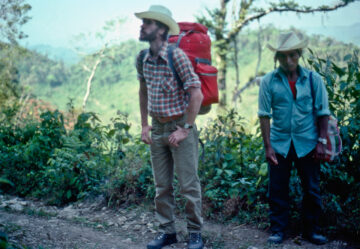

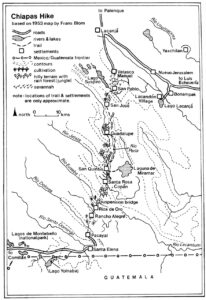

Han Stricker, a 25-year-old Swiss physician, and I came to the Mexico-Guatemala border to begin a nine-day, 160-kilometer trek into the Selva Lacandona. The selva – the Spanish word for jungle – is named for the Lacandon Indians who sparsely inhabit the area.

It is a vast, roadless and unmapped territory bordered by the Rio Usamacinta on the east, the Rio Jatate to the west, and the Mayan ruins of Palenque to the north.

Hans and I travelled by bus at an average speed of 20 kilometres and hour for two and a half hours over rough road from the Lagos de Montebello to Santa Elena where the Santo Domingo river makes a deep bend to the Guatemalan border. From Santa Elena we took even more jolts in the back of a dump truck to Pacayal. Along the way we encountered a massive road construction project.

New American trucks and bulldozers were slowly inching their way through nearly impenetrable rain forest to build a new highway east along the Guatemalan border then northwest to the fabled ruins of Bonampak. Our ride stopped at the road’s end – the end of civilisation as we know it – and we jumped off the back of the truck while the driver fired up a bulldozer and began pushing back the jungle.

Rather than waiting a few years until the completion of the highway, Hans and I began walking north to Bonampak, the site of some Mayan ruins and our goal.

An Indian carrying his load with a tumpline led us to the village of Huistan. Hans and I struggled to keep up with the nimble-footed Indian as we climbed the undulating trail under a hot midafternoon sun. Both Hans and I started to wonder if our adventure was such a good idea. How would we survive trekking through the rugged terrain in such heat? Shortly after we reached Huistan that question was answered :a tranquil river lined with shade trees hosting bromeliads – the Rio Delores. After a refreshing swim in the river we felt reborn and were once again eager to continue our journey.

Day 2 – 29 March

Rio Delores to San José Esperanza

The next morning, a heavy fog shrouded the Rio Delores valley and seemed to immobilize the jungle.

We were awoken by voices outside of our tent and to find a pair of Mexicans trying to lead their horses to water. A large raven-like bird flew overhead, its wings slicing through the fog, every wing flap audible.

We crossed the river on a new suspension bridge and entered the village of Nueva Posa de Rico.

By 0730 as the fog began to lift, sweat already poured through my pores. Fortunately, the Selva Lacandona is well watered and in two hours we reached a cool bubbling stream.

Due to the intense heat and humidity, Hans and I frequently spent the hottest part of the day in or near water and saved the hiking for early morning and late afternoon.

After a refreshing swim, we passed quickly through the new colonias – or settlements – of San Tomás Nuevo and Ranche Allegre. After passing through the new settlement of Riza de Oro we hiked through several hot, open milpas.

***

Milpas – the Spanish word for cornfield – are appearing at an alarming rate throughout the Selva Lacandona.

Like most rain forest dwellers, the Tzeltal Indians living at Riza de Oro practice slash and burn agriculture. In the spring, the farmers clear a small one-hectare plot of virgin jungle. Armed only with a machete, a farmer will spend 20-40 days at slashing down a fortune in hardwood timber. After allowing the vegetation to dry it is burned in May. Burning releases the organic nutrients that are suspended in the canopy of the trees and makes them available to the crops. Shortly after the burning, the Tzeztal farmer plants corn and beans in the ash-rich soil. The yield is good for two maybe three years then the soil is exhausted. The campesino merely moves to another location and slashes down more jungle.

The tropical rain forest is a fragile, impoverished environment, but its lush vegetation creates the illusion of unbounded fertility. The Lacandon jungle is actually one of the world’s richest jungles growing on the world’s poorest soil. The soil consists, usually of a few centimetres of topsoil over sterile, white cretaceous limestone. Over this topsoil there are a few more centimeters of extremely rich mould. The majority of nutrients are suspended in the living canopy of trees and vegetation that shades the thin and rapidly leached soil. Burning releases these nutrients.

Slash and burn agriculture provides very well for small populations, such as the Lacandons, who lived in balance with the environment. But the Selva Lacandona was not a place for the thousands of agaristas who were immigrating to the jungle. Since 1940, more than 80,000 peasants had migrated into the lowland Chiapas jungle in search of land and new lives by 1980.

***

After Riza de Oro though we entered a world that time had hardly changed – our first glimpse at the virgin rain forest – a tract of forest which the colonists had not yet destroyed.

It was the same forest where a civilisation flourished for six centuries until the 10th century. The classic Maya practiced a highly diverse, intensive yet sustainable agriculture that enabled them to support their population for hundreds of years.

Yet the jungle Hans and I now hiked through survived the chain saws of the mahogany cutters. However after a two-hour hike, it came to an abrupt halt, and we entered another chapter of the exploitation of the Selva Lacandona as we entered San José Esperanza.

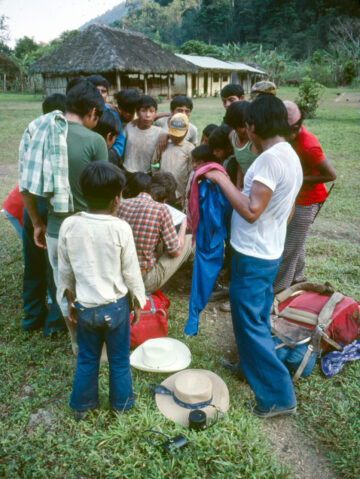

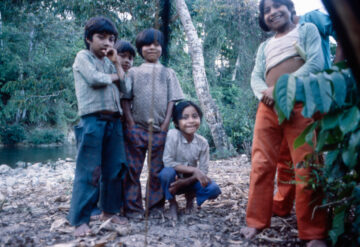

We rested by a small creek that flows through the village and through the corner of my eye I could see small groups of Indians gathering in the distance to watch us but too timid to approach us. A young man finally rose to leadership and walked toward us followed by a band of curious children. He asked the usual questions: Where do you come from? Where do you live? Why are you hiking to Bonampak?

More villagers crowded around us as news of our arrival spread. Another young Indian man came and immediately became the leader. He was the world traveller, having been to Baja California and Guatemala and therefore knew how to respond to foreigners.

The welcoming committee decided that we should sleep in the school. They lined up school benches for beds. By this time, the men had finished their days’ work in the fields and came to check out the gringos. Again we answered their endless questions. Hans did all the speaking since his Spanish was much better than mine and I merely grinned, nodded and laughed at the proper cues.

I looked around and noticed the small hut was filled with people. Children had climbed the walls outside to get a look at their village’s visitors. The last foreigners who passed through were an Israeli man and his wife 18 months ago.

The Tzeltals who live in San José Esperanza are recent migrants to the Selva Lacandona. Due to increasing population density and soil degradation the Tzeltals left their homelands throughout Chiapas during the 1950s and 1960s to start what has been called the Mayan Migration. At great personal sacrifice they carried their possessions on their back and moved into the Lacandon rain forest. Those who survived carried on their slash and burn farming techniques on new land. San José Esperanza was founded in 1969 and has since become a healthy, self-sufficient village.

Like most of the villages we passed, San José grew only corn, beans, bananas and coffee. Enough coffee was grown to allow for export which provided money to buy clothes, boots and machetes.

We slept peacefully in the open hut due to the efforts of Julio, whose job in the village was malaria eradication. We learned that the men formed part of a malaria fighting group. They travelled in the area with mules, helmets and DDT to try to combat the mosquitoes and make the area more hospitable for humans. They hadn’t been successful as malaria was still common. In previous years there had been several deaths caused by mosquitoes. We encountered no mosquitoes.

Day 3 – 30 March

San José Esperanza to Rio Jatate

In the morning, the men of the community who acted as our hosts gathered in the school hut to watch us pack our bags. Each gadget we put in our bags rose questions and whispers amongst them … How much does it cost? How does it work?

While the sun was still low and a mist in the valley, we gave our farewells to each of the men, asked directions and began another long day of hiking.

One hour later we were already cooling off our sweaty bodies in the Rio Euseba. Ahead was a gruelling four-hour waterless trek over the Sierra Colmena. The rocks, vines, roots and steepness of the trail made it difficult to appreciate the brilliant flowers that grew along the trail. All I could think of was the next watering hole. The dense jungle gave us a claustrophobic feeling.

As the sun was setting that evening, we arrived on the savannah of San Quintin. It felt wonderful to be able to see anything beyond a few metres. We raced to get to San Quintin by dark. Since San Quintin had an airfield many of the luxuries of civilisation were flown in. The thought of a big meal propelled us. We decided to camp at the Rio Jatate – a short walk from San Quintin for that long sought after meal.

Yet our hopes vanished when I was unable to cross the suspension bridge. A cable had broken loose, and the walkway was perpendicular to the water. Determined as I was, I tried wedging my shoes into cracks in the planks and hanging tightly to the cable. It became impossible and I turned back.

We settled for bouillon and instant beans for dinner.

Mosquitoes were merciless that night and to add to our discomfort it was hot and sticky. After settling down in the tent and trying to sleep, Hans and I were just too hot and ran out of the tent and plunged into the river.

That night I slept little. My body was covered with chigger and mosquito bites and I had a sensation of insects crawling on me all night and I constantly swatted imaginary insects.

Day 4 – 31 March

Rio Jatate, San Quintin, Lago Miramar

At dawn we heard voices outside the tent as some Mexicans debated how to cross the bridge. We emerged from the tent and watched them hanging on to the cables while inching across the swift river. We decided we had no alternative but to cross as they did. As I had a fear of heights I was terrified as I inched across with my heavy backpack pulling me backwards. Sweat poured down my face and stung my eyes, my knuckles white from grasping the cable. But after what seemed an eternity both Hans and I – and our heavy bags – made it across the river.

Our destination for the day was Laguna de Miramar – a mysterious lake which was a two-hour walk away. We had hoped to get our first encounter with the Lacandon Indians who we had heard lived at the lake and we were hoping to get visit some islands where we hoped to find some relatively unknown Mayan ruins. We thought it would be an easy two-hour walk once we crossed the Jatate River.

Hans and I wandered aimlessly through an overgrown milpa searching for a trail to the lake. The secondary growth of thorns and vines made travel very difficult and provided good cover for poisonous snakes. We set our packs down and went in different directions looking either for people or a trail.

I discovered a woman who gave me unclear directions to the lake. After another hour of wandering the milpa we finally found a man who put us back in the jungle on the right trail. The hike that followed was agonising. The mosquitos were so bad we couldn’t sit for long – we just kept moving and swatting. I thought of the airstrip in San Quintin and was tempted to once and for all get out of this green hell. In heavy anticipation of the lake, we expected each turn in the trail to reveal the lake. But we hiked for three hours not even knowing for sure if we were on the right trail. But then suddenly the jungle opened up and revealed a shimmering body of water.

It is amazing how a swim in a cool, clear lake can so quickly revitalise the body and lift the spirits. Hans and I swam out toward the middle of the lake to look for signs of any clearings or settlements. There were none. The jungle-covered mountains stopped abruptly at the lakeshore making a terrain too steep for settlement. Yet on the east bank a plume of smoke caught my eye and I noticed the slope there appeared to be level. We decided that’s where we needed to get to the next day.

The water was an emerald colour and was so clear I could read a book on the bottom of 3 metres of water. The lake bottom was a very fine silt and as I walked a puff of silt would rise as if I were walking on the moon.

We returned to our packs and set out to look for a camping spot. Shortly we found a small grassy clearing on a superb sandy beach. We were baffled by a basket loaded with books written in English and Spanish. Could they belong to Villi – the German who lived on the lake? There were footprints in the sand and a rotting dugout canoe, but the trail ended here. The mysteries could wait for the morning.

During the night we were awoken by a distant eerie, howling noise. Shortly after the wind kicked up and violently shook our little tent as if the Mayan Gods were rebelling against us.

Day 5 – 31 March

Lago de Miramar to San Quintin

In the morning we began an expedition to investigate reports we had heard of a village, Mayan ruins, caves and islands. We followed a trail and soon heard voices and discovered a woman and four children waiting by the lakeshore by a dugout canoe.

She and her family were returning from San Quintin where they had flown to San Cristobal for medical care for the children. Her husband came later carrying mud to patch the canoe and a large bag on his back supported by a tumpline.

We told him of the eerie howling noise we heard the night before and he laughed and said it was merely a troop of sarahuate or howler monkeys. He told us that there actually was a small village on the other side of the lake, but there was no trail leading to it. Boating was the only way, and his canoe was obviously full. He knew the man who we were told could act as a guide, but he had left the lake for several weeks. Bad luck for us, but we were perfectly content to spend the rest of the morning and early afternoon at the late and then hike to San Quintin. Later I discovered that there actually were a number of Mayan ruins on several islands and some interesting caves.

The return trip to San Quintin took only two hours. Before crossing the Rio Perla a man claiming to be an official stopped us and demanded to see our tourist cards. He claimed it would cost 100 pesos to pass through. This, of course, was ridiculous and we were stubborn. The ‘official’ was supported by his friends. After a long, half hour quarrel we were allowed to pass since it was our first trip to the village – but if we returned, we would have to pay.

Day 6 – 2 April

San Quintin to Guadalupe

The next day’s hike to Guadelupe was along the Rio Perla. At least it was supposed to be. Hans and I got thoroughly lost again after we misinterpreted some directions that were given to us. The familiar sound of the machete chopping wood guided us to a hut. We asked if we were on the trail to Guadalupe and when a puzzled look came over the boy’s face we knew we were lost. We ended up paying the boy’s older brother to guide us to the trail. For an hour he swung madly with his machete through thick jungle until we were finally on the right path.

Without a doubt the most frustrating part of the trip was getting lost. We could deal with the heat and insects but not losing directions in such an unfamiliar environment. We found our destinations mainly by asking directions and by compass since trail maps of the area were simply not existent.

At one point we had to cross the Rio Perla. The suspension bridge had long ago rotted away and was unusable. The current was swift and deep so we could not ford it. Hans looked to the other side of the river and saw a canoe and before I could respond he had stripped to his underwear and began swimming across. He grabbed the canoe and I immediately realised the Swiss didn’t have much of a knack for paddling. He courageously tried to cross the stream, but the current brought him well down the shoreline and he had to tow the canoe upstream. I laughed at his efforts and told him I’d better paddle the return trip because in Wisconsin all children come out of the womb clinging onto a canoe paddle. The dugout canoe was not as responsive as the superlight fibreglass canoes I was accustomed to but I merely had to point the bow slightly upstream and use my paddle as a rudder. We made it straight across without having to even paddle. Hans was impressed.

We were absolutely exhausted after a 12-hour hike when we arrived at the village of Guadelupe. Strangely, we did not feel welcome in this community. After visiting a few huts, we found someone who would sell us some tortillas and beans. We were starving. I picked up a tortilla only to discover I was sharing it with a family of cockroaches.

Day 7 – 3 April

Guadalupe to San José

The hike from Guadalupe to San José was a real treat. A Mexican petroleum company had painted red blazes on the trees along the route. Without the worries of finding directions, we were able to enjoy the jungle world we hiked through.

I became aware of the music of the jungle. A persistent, low hum of insects and frogs provide the background music. Although always present, I learned to tune out this hum, except at times when it was literally ear piercing. Occasionally a bird or monkey would scream out breaking the silence. I often stopped walking and listened to the complex musical arrangement that was being played. My pounding heart provided the rhythm.

The jungle no longer appeared as an inimical wilderness or as a snake with a hundred thousand coils. Rather it appeared as a gentle purring kitten waiting to be petted. The heat and insects no longer disturbed me and I now felt as if I were walking in the tropical plant section of a botanic garden.

At one point, when Hans and I had stopped for a rest, we heard a shrill scream and heard people approaching us. From down the trail I could see three people approaching – the two Indians in the lead wore brightly coloured Tseltal textiles. Behind them, I saw a teen age boy with long black hair wearing a knee-length white tunic. He carried a rifle in one hand and a machete in the other. The trio paid us little attention and seemed to be in a hurry. But I couldn’t take my eyes off the boy with the long black hair – I was finally seeing a Lacandon Indian – a direct descendant of the Mayas. The boy was equally fascinated in me and as he silently walked past, our eyes locked as we were both fascinated at seeing such a different form of humanity. I watched them disappear into the jungle and then looked down to see my camera draped around my neck. It was my one and only sighting of the Lacandon Indian and the camera’s eyes had remained closed.

Shortly after we had arrived in San José and had chosen our campsite, a welcoming committee gathered around us. The group stared at us and whispered amongst themselves as we set up the tent and bathed in the river.

One boy came to me and gave me a stack of warm tortillas wrapped in a towel. ‘A gift’, he said. Later we went to his hut and gave his mother a kilo of rice to prepare for ourselves and her family.

We sat at the table of the hut and ate our rice, beans, tortillas and coffee by candle light. We still had a group of camp followers who sat in the hut and watched us eat. The woman of the hut squatted near the hearth, rarely taking her eyes off us.

Only occasional whispers and the setting down of our coffee cups broke the silence. Our offer of payment for the meal was refused; they were quite satisfied with the entertainment we provided.

Day 8 – 4 April

San José to San Pablo

The next day the jungle exposed another face. The trail was rough, steep and uncertain. This time there were no campesinos to ask directions. We relied on the compass. Yet even that was misleading – our general direction was supposed to be northeast but many times the trail led us in a south-westerly direction.

Just after sunset we arrived in San Pablo. Yet we were astonished – no one was there to greet us. Surely every village knew of our coming well before we arrived. We walked into the village and discovered it was recently abandoned.

Voices filtered through one of the huts and we found two Indian women. We learned that everyone had been forced to leave the village and move to Manuel Velasco.

It was the Mexican government’s attempt to resettle the Indians and create an organised agricultural plan. Until then, farmers merely moved into the Selva Lacandona and claimed land was theirs solely by occupation.

In theory, the resettlement could save the Selva Lacandona, but time was the critical factor. The program wasn’t being carried out quickly enough.

We camped in the ghost town of San Pablo – our last night in the Selva.

DAY 9 – 5 April

San Pablo to Manuel Velasquez

In the morning we followed a wide trail that had seen heavy use – a trail that had felt the feet of many campesinos carrying their limited life’s possessions on their backs to start a new life in the government settlement. And now it felt the feet of two gringo backpackers with their final goal in sight. Our guidebook promised us an easy three-hour walk but as always it was far from that. We knew our destination lay to the northeast so I checked the compass every time we reached some fork in the trail.

Eventually after nine days in the jungle we reached a road, and our pace quickened as we dreamed of cold frothy beers.

As we walked into the government settlement of Manuel Velasco all eyes were on us. The residents could hardly imagine where a pair of backpack-clad gringos would be coming from. As always as soon as we put our packs down a group gathered around us and asked the usual questions. We told them we had come from the other side of the Selva but they assured us there was no trail from San Quintin. We begged to differ with them as we had somehow found our own trail. We told them of our adventure and they listened intently and lit up when we mentioned a village where they might have come from. I could tell they longed for their life in the jungle. ‘La selva es muy bonita’, they all said. The jungle is beautiful. They seemed unhappy in this dusty government town and yearned to return to their homes.

At Manuel Velasco, we were able to find a truck leaving for the main road. We jumped in the back and joined a turkey and a burro and tried to find a spot on the flatbed not covered with manure. The truck pulled out and then stopped. We saw a man running after us. The truck started again and the man continued to run after us. Once more we started, and the man ran. Finally, there were grins on everybody’s face and the driver got out and took the burro from the truck. The negotiations were completed. He sold the burro for 500 pesos. We continued on our journey – but now it just the turkey and the gringos.

The truck left us at a roadside stall on the highway to Palenque and the owner allowed us to sleep in the barn. He told us a bus to Palenque would pass at 5 am. We got up at 4.30 and were told that the bus had already passed. We stood by the road in the misty dawn and eventually a curious driver in a car stopped and brought us to Palenque.

A few kilometers out of Palenque, Hans noted the first power and phone poles. We were approaching civilisation or in the words of the environmentalist and author Edward Abbey – syphilisation. Chaos. Filth. Noise. People. And ridiculously dressed tourists. Palenque is home to some of the greatest Mayan ruins but neither Hans nor I could stomach the idea of spending time in syphilisation. Fresh out of the jungle we just weren’t ready for it and were suffering from civilisation shock. Instead we found a bus heading back to our starting point – the mountain village of St Cristobal de las Casas.

On the bus we met an American traveller who brought us up to date with the world news while we were incommunicado in the jungle. US President Ronald Reagan had been shot but survived an assignation attempt and a group of union members called Solidarity had organised a massive strike in Poland thus putting the Soviet Union on edge.

Hans and I weren’t too interested in hearing of the mess the world was in. We sat silently in the back seat of the bus and stared out the window as cars and trucks raced passed us along a highway littered with rubbish. We forgot about the exhaustion, sweat, sunburn, insect bites and lost directions of our journey and reflected on the incredible adventure we had just shared. We had overcome physical hardships and seen a part of the world which few outsiders had seen. We had shared food with Indians and laughed with them and gazed out at starry skies with them. We had forded rivers and climbed mountains only to find another river and mountain. And we had experienced something we knew was part of a disappearing world and an adventure which we knew our children would never be able to experience.

I looked at Hans gazing out the window on that bus and knew he had the same thought as I did.

The Mayan spirits were beckoning us. We wanted to turn around and return to La Selva Lacandona.

[NOTE: This story was written in its present form in August 2013 for a presentation I gave. It draws heavily on my journal and a draft of a story I wrote in May 1981 with the hopes of publishing it in Outside magazine so I have dated this as being written in 1981.]