I took a walk through time recently. Matter of fact, I walked thru a period of the Earth’s history that occurred 10,000 to one million years ago. And I witnessed the remnants of a tremendous battle that occurred against a frozen invader.

I walked a portion of the Ice Age Trail.

I arrived at the Intersection of Forest Road 558 and the trail at dusk on a warm mid-October day. I had hitchhiked to the southern border of the Chequamegon National Forest in Taylor County in northern Wisconsin from Stevens Point, 140 kilometers to the southeast.

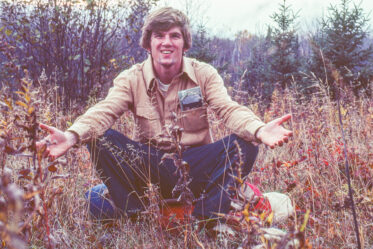

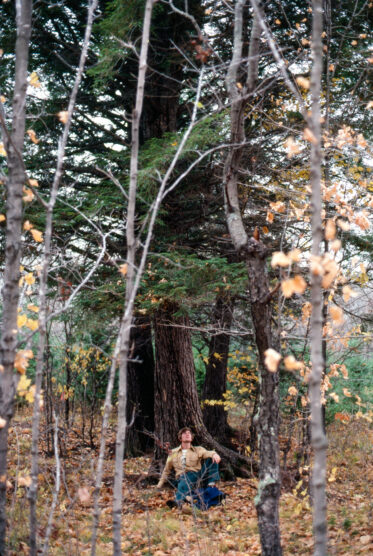

I shouldered my backpack and soon all five of my senses were searching out new sensations. Every ten paces I stopped to explore something. I listened to a hairy woodpecker pounding away, I felt a slimy mushroom, I tasted a wintergreen berry, I smelled the fragrant air of the coniferous forest, and I gazed into the setting sun.

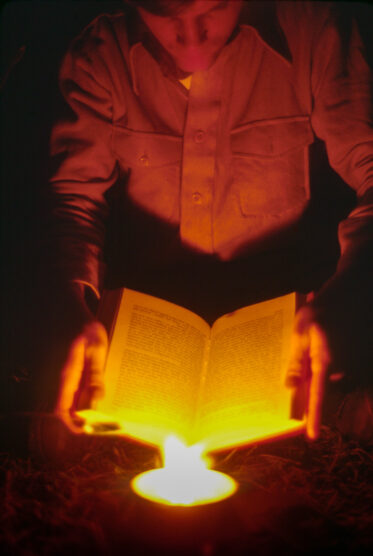

After walking a half mile, I found a campsite – a meadow overlooking a valley. Three crows announced my arrival and sent a deer dashing for cover. As I hiked to a creek a slate-colored junco sung out to me. I “squeaked” and soon was surrounded by juncos. Supper was by candlelight as the hiss of my small stove pushed the silence away and the candle fought the encroaching darkness.

An owl called out from far away, I called back and was answered. For a long time I listened-and contemplated over the night sounds, then retired.

***

The Ice Age Trail in Taylor County is a 48-mile completed segment of a proposed 1,000-mile trail that stretches along the fringe of the farthest advance of the last or Wisconsin Glacier. The trail follows a course from Sturgeon Bay south, north and west to Interstate State Park on the Minnesota border.

***

There was a rustling about my tent at dawn and a chickadee called out—”chick-a dee-dee.”. I was anxious to explore so I slipped on my boots and crawled out of the tent.

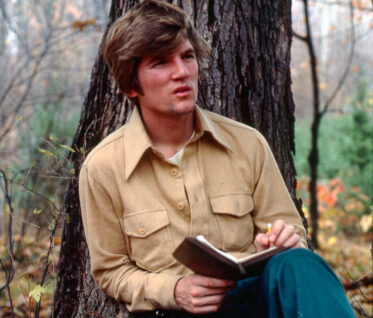

I find no joy in carrying a fully loaded backpack, so armed with only a notebook, bird book and camera equipment, I set out to explore.

Wandering off the trail I came to a beaver dam – something I would see in abundance on the trip. The water was a rusty brown due to tannin emitted from the numerous tamarack trees in the area. I walked for a good two to three hours and made a circular trip. Just before I reached camp, I found wild ginger growing which I dug up to make ginger milk.

Back at camp I packed my gear and left no sign of my stay except matted grass.

I walked a mile down the trail, then paused and thought of that distance. Then I looked up and imagined that distance.

That was the thickness of the continental glacier which left the glacial deposits I was hiking on. I shuddered at the thought of the tremendous grinding, crashing, and crushing forces that occurred.

My pace was slow as I stopped to nibble on partridgeberries and wintergreen berries along the way and rested after every climb on the hilly trail. At times I was so captivated by the scenery that I continued, walking down a logging road when the trail had turned off long before.

Several kettle lakes formed by huge blocks of ice left by the melting glacier dotted the area. I choose to camp by one called Lake Eleven. What an awful name, I thought, for such a wonderful lake. It is hard for me to understand why man has to name everything, but it is totally incomprehensible to me why he would put a number to a lake. I found a campsite on the east side of the lake and was again welcomed by a flock of juncos and chickadees.

I ate my supper like I would a TV dinner and watched the sun slowly sink. The tamaracks caught the last rays of the sun and reflected their honey-colored image off the placid lake. I tuned my ears into nature’s radio and heard a rodent squeal after falling prey to an owl.

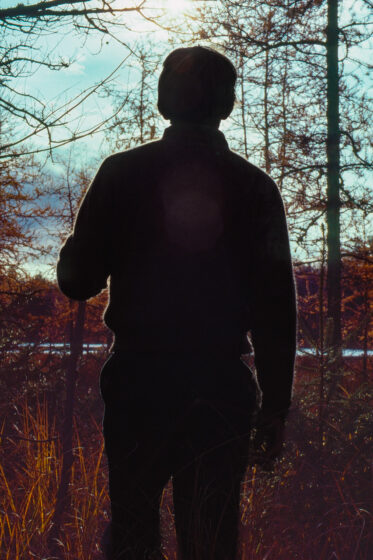

It occurred to me that I had not seen nor spoken to any human since the previous afternoon. That comforting thought brought a smile to my face as I eased into sleep.

A thunderstorm passed by, and rain fell most of the night. I felt secure and safe in my tightly pitched tent.

I had two visitors the next morning. The first was a noisy kingfisher who sat on a perch 15 meters from my tent. The next was a human on a motorcycle. Damn, I thought, I wasn’t ready for this.

Fortunately the man drove by on a logging road, and I was hidden from his view.

The sun was still low in the sky and, not wanting to waste the morning hours, I quickly ate some bread and cheese and began a walk around the lake.

Halfway around the lake I was prevented from going further by a stream. But I knew that the beavers, just like the Army Corps of Engineers, wouldn’t pass up the opportunity to put a dam across it. And, lo and behold, a short walk upstream revealed a dam!

Once that barrier was crossed, I reached another stream. Yet this one had no dam; it led to a small kettle lake. I walked to the lake’s edge and found myself on a carpet of floating sphagnum moss. For a moment I stood spellbound by the artistry of the lake. Colors were splashed everywhere. The tamaracks splashed their golden colors, the sphagnum their amber and red, the pitcher plant their green and crimson and the cranberries their scarlet. Sunlight glistened off rain drops collected on the needles of the black spruces.

I was in a state of ecstasy and wanted to exalt my newfound joy. I felt higher than any drug would get me. And it was here that I discovered that Wisconsin really is the glacier’s art gallery.

As I revelled at the splendor to the scene, I felt indebted to Ray Zillmer, the late Milwaukee attorney, outdoorsman, and hiker whose foresightedness and concern led to the establishment of the Ice Age National Scientific Reserve. Ray Zillmer had a dream, and that dream was to create an 800-mile long national park to preserve the evidence of the Great Wisconsin Glacier and to tell a tale of how out land was formed. And I felt indebted to the countless groups and individuals who developed, cleared and marked the trail and whose unselfish labor I enjoyed.

I walked back to camp and was brought out of ecstasy by two human visitors – hunters. What were they hunting for? Anything that flies.

I packed my gear and hiked the three remaining miles to County Highway M. I walked in the rain, but it didn’t bother me. My mind wasn’t on the trail – it was in another world, another time, another age.

The Ice Age ended 10,000 years before, but I felt I had walked right back in time and was in the midst of it.

***

Originally published in Bio-Logic, the Official Organ of the Tri Beta Biology Club in November 1979

!["...A thunderstorm struck. Fortunately, I took extra precautions and set my tent up well. ... It rained hard for most of the evening. I fell asleep and all was quiet except for an occasional animal creeping around the tent...."

[Next morning] "...A kingfisher flew to a perch 15 meters from me. I didn’t want to waste the morning hours so I grabbed a cheese sandwich and began hiking around the lake...."](https://michaelmajor.com.au/wp-content/uploads/cache/2025/04/1979-10-21-Chequamegon-01/998017783.jpg)