On maps, Kyrgyzstan looks like a country made of ridgelines. Landlocked, mountainous and wedged between larger powers, it had intrigued me for years. I finally visited in July 2023 to photograph alfalfa. What filled my viewfinder instead were ‘jailoo’ grasslands, towering mountains, vast skies and horses grazing as if little had changed in centuries.

Kyrgyzstan is often described as the most mountainous country in the world. More than 90 percent of its territory lies above 1,500 metres. The Tien Shan range dominates the map, with peaks rising above 7,000 metres along the Chinese border. On paper it’s contour lines. On the ground it’s altitude, light and space.

My Crop Trust and local colleagues entered at the Kazakh–Kyrgyz border at Karkara in the northeast. As I entered the Karkara Valley at about 2,000 metres, I pointed my camera to the east toward the Kungey Ala-Too Range of the Tien Shan. Summer rangeland was bursting into purple bloom, backed by forested slopes and high alpine rock. To the west, a herd of horses galloped through pastures backlit by the sun.

Welcome to Kyrgyzstan.

From there we travelled west along the north shore of Issyk Kul, the second-largest alpine lake in the world after Lake Titicaca. Despite sitting at 1,600 metres, it never freezes, thanks to its depth and slight salinity. We stopped to cool our bodies and wash away the road dust in its clear, bracing waters. After days of heat and impromptu alfalfa stops, it felt like a reset.

We continued along A363, the main artery around the lake, which connects small towns and irrigation schemes that date back decades. Irrigated plots of alfalfa sat green against the dust and rock. I had come for those fields, but my eyes kept lifting to the skyline.

Much of A363 was developed during the Soviet period, when Moscow invested heavily in linking remote republics with sealed roads, collective farms and research stations. Under Soviet rule, borders were fixed, collectivised agriculture replaced clan-based herding structures, and Russian became the administrative language. Much of the irrigation infrastructure and formal agricultural research I had come to see traces back to that era. Independence in 1991 did not erase older patterns. Families still erect yurts on summer pasture. Horses are still wealth. The seasonal rhythm endures.

We detoured off the highway to spend a night in those yurts and climbed north to around 2,000 metres, following the valley to the road’s end at Semenovskoye Gorge. Kyrgyzstan’s summer pastures, known as ‘jailoo’, have supported herding for centuries. Families still move livestock to high grazing grounds much as their ancestors did along Silk Road corridors.

It was late afternoon when we reached the road’s end. Vehicles descending toward Issyk Kul threw up long plumes of dust that hung in the low sun, mountains layered behind them. In monochrome the scene felt almost timeless – a single four-wheel drive tracing a dirt road through a vast upland basin.

A driver offered to take us the remaining distance to Besh Karagai, our accommodation for the night, but after hours in the car a few of us chose to walk the last three or four kilometres with the setting sun behind us. It felt good to move under our own steam. Horses grazed in loose groups across the pasture, barely lifting their heads as we passed.

The Kyrgyz word ‘at’ means horse, and horses remain central to national identity. Historically they were transport, wealth, warfare and sport. Even today, games like kok-boru – a fierce mounted competition – are played at festivals and weddings. In a country of roughly seven million people and nearly a million horses, the horse still carries real economic and cultural weight.

As the sun dropped lower it struck the horses’ coats and turned them a deep burnished gold. In gaps between the hills, we could see Issyk Kul in the distance, a pale strip of blue on the horizon. There were no crowds, no tour buses, no noise beyond wind and the occasional snort of a horse. Just pasture, light and altitude.

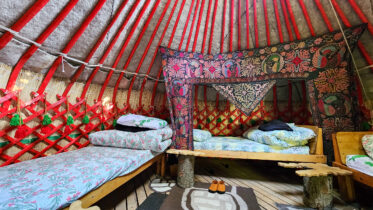

At Besh Karagai camp we slept in yurts, the traditional felt dwellings of nomadic pastoralists. The circular wooden frame and thick wool insulation are practical responses to climate and elevation, refined over generations. Inside, it was cool and comfy.

The Kyrgyz are a Turkic people whose roots stretch deep into Central Asia. For centuries they lived as nomadic pastoralists, moving with herds across mountain systems that ignore modern borders. Their features often reflect the meeting point of East Asian, Mongol and Turkic lineages shaped by migration and trade along the Silk Road.

We returned to the A363 and travelled toward the capital city of Bishkek, stopping the car whenever we saw alfalfa along the road. We took a break from alfalfa and spent a night at the gateway to Ala Archa National Park, where the mountains closed in and hikers are alerted to ant crossings. Glacial rivers ran fast and opaque. Birch and pine clung to the slopes before giving way to rock and scree.

We looped back to Kazakhstan via Korday after only a tantalising glimpse – enough to know I had not seen nearly enough of Kyrgyzstan. It felt less like a destination checked off and more like an introduction – a mountainous Central Asian country still shaped by horses, pasture, infrastructure laid down in another era, and a people whose relationship with land runs far deeper than any map.